(Reprinted with permission of the author, DIANA KUNDE)

(Reprinted with permission of the author, DIANA KUNDE)

Sun, Nov. 5, 2005

Special to the Dallas Morning News

FORT WORTH—What do you answer when your toddler asks, “What’s this?” What’s likely to follow when a politician begins a sentence with: “The fact of the matter is … ?”

And what do these questions have to do with one another?

Welcome to the world of Steve Stockdale, executive director of the Institute of General Semantics. Mr. Stockdale, 52, became interested in general semantics in graduate school at Texas Christian University after graduating from the U.S. Air Force Academy. After a career in defense electronics with Texas Instruments Inc., he was researching new directions when he began volunteer work for the institute.

The institute was formed by the merger of two long-established semantics groups – one in California, one in New York – in 2004. Mr. Stockdale became its director, steering the nonprofit through its relocation to temporary quarters in Fort Worth. Last fall, it moved into a renovated 1932-era grocery store in the city’s historic Southside neighborhood.

It’s his mission, he says during an interview at the institute, to raise the profile of this relatively little-known field of study.

For instance, he’s teaching a course at TCU and working with advanced-placement English teachers from the Birdville school district.

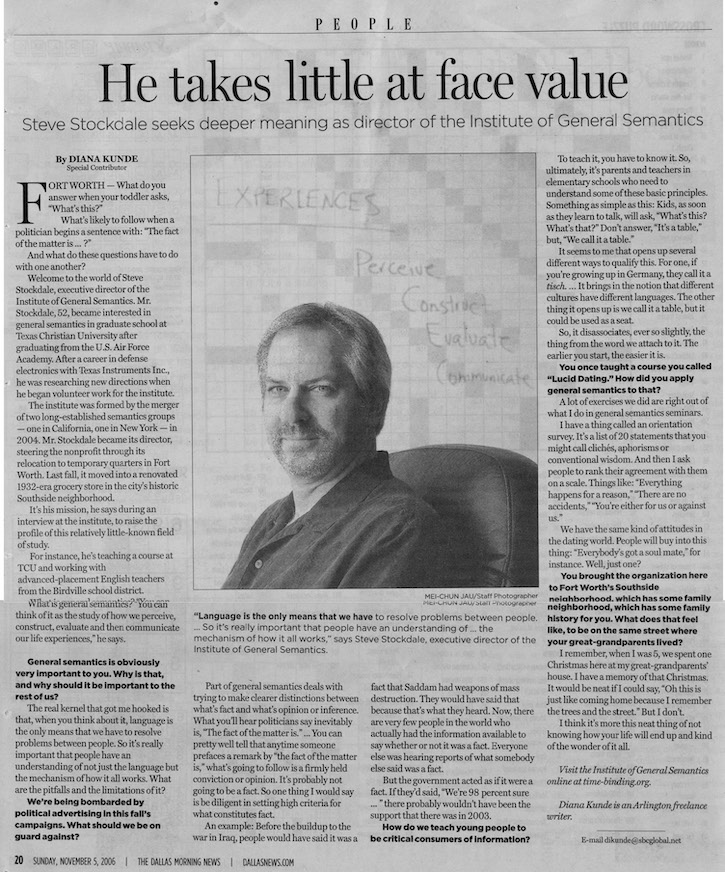

What is general semantics? “You can think of it as the study of how we perceive, construct, evaluate and then communicate our life experiences,” he says.

General semantics is obviously very important to you. Why is that, and why should it be important to the rest of us?

The real kernel that got me hooked is that, when you think about it, language is the only means that we have to resolve problems between people. So it’s really important that people have an understanding of not just the language but the mechanism of how it all works. What are the pitfalls and the limitations of it?

We’re being bombarded by political advertising in this fall’s campaigns. What should we be on guard against?

Part of general semantics deals with trying to make clearer distinctions between what’s fact and what’s opinion or inference. What you’ll hear politicians say inevitably is, “The fact of the matter is.” … You can pretty well tell that anytime someone prefaces a remark by “the fact of the matter is,” what’s going to follow is a firmly held conviction or opinion. It’s probably not going to be a fact. So one thing I would say is be diligent in setting high criteria for what constitutes fact.

An example: Before the buildup to the war in Iraq, people would have said it was a fact that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction. They would have said that because that’s what they heard. Now, there are very few people in the world who actually had the information available to say whether or not it was a fact. Everyone else was hearing reports of what somebody else said was a fact. But the government acted as if it were a fact. If they’d said, “We’re 98 percent sure … ” there probably wouldn’t have been the support that there was in 2003.

How do we teach young people to be critical consumers of information?

To teach it, you have to know it. So, ultimately, it’s parents and teachers in elementary schools who need to understand some of these basic principles. Something as simple as this: Kids, as soon as they learn to talk, will ask, “What’s this? What’s that?” Don’t answer, “It’s a table,” but, “We call it a table.”

It seems to me that opens up several different ways to qualify this. For one, if you’re growing up in Germany, they call it a tisch. … It brings in the notion that different cultures have different languages. The other thing it opens up is we call it a table, but it could be used as a seat. So, it disassociates, ever so slightly, the thing from the word we attach to it. The earlier you start, the easier it is.

You once taught a course you called “Lucid Dating.” How did you apply general semantics to that?

A lot of exercises we did are right out of what I do in general semantics seminars. I have a thing called an orientation survey. It’s a list of 20 statements that you might call clichés, aphorisms or conventional wisdom. And then I ask people to rank their agreement with them on a scale. Things like: “Everything happens for a reason,” “There are no accidents,” “You’re either for us or against us.”

We have the same kind of attitudes in the dating world. People will buy into this thing: “Everybody’s got a soul mate,” for instance. Well, just one?

You brought the organization here to Fort Worth’s Southside neighborhood, which has some family history for you. What does that feel like, to be on the same street where your great-grandparents lived?

I remember, when I was 5, we spent one Christmas here at my great-grandparents’ house. I have a memory of that Christmas. It would be neat if I could say, “Oh this is just like coming home because I remember the trees and the street.” But I don’t. I think it’s more this neat thing of not knowing how your life will end up and kind of the wonder of it all.

Visit the Institute of General Semantics online at generalsemantics.org.

Diana Kunde is an Arlington freelance writer. E-mail dikunde@sbcglobal.net

© 2006 Diana Kunde. Reprinted with the permission of the author. Photo by Mei-Chun Jau, Staff Photographer.